Given the choice between the experience of pain and nothing, I would choose pain.

– William Faulkner

Hmm, 400 – a brevet from an evil mother and a bad father. Stepmother of all brevets. Almost every randonneur will tell you that it is the most difficult brevet from the BRM series. But why is that the case? Let’s see…

300 + 100 = ?

Eh, we can’t look at 400 that way! First of all, regardless of the fact that you already have the experience of riding a 300, you now need to repeat it all over again and only then add another 100 km on top of it. Furthermore, having previously completed a brevet or a 200 km route in general, it no longer seems so impressive to you and for some uninformed observer, who has no sense of distance, it may also not be an epochal endeavor. 300 is already a more serious number, because even by a car it takes a lot of time to cover that distance along the routes on which brevets are ridden. But 400 km? 400 is simply a huge number, whoever and however one looks at it.

But let’s first see why ride a 400 km brevet at all? The BRM400 is part of a series of 200, 300, 400 and 600 km long brevets to be completed in the year when Paris-Brest-Paris is being run, as qualifications for it (along with BRM1000, which can replace one of shorter brevets). Also, if you want to achieve an additional randonneur title, such as Randonneur 5000, you need to complete this entire series, with many other endeavors on top of it.

In my opinion, the above facts are, in principle, the only reason to ride this distance at all. Neither does it present an interesting “round” number – like 500, nor is it a drastically greater achievement than riding a 300, nor does it play an important role in preparations for a 600 ride, nor does ti carry an interesting deadline, such as 24 hours. Moreover, the limit is 27 hours, which is the biggest issue, i.e. the challenge that this distance presents.

If we look at the 200 km brevet and its limit of 13h30, for an additional 100 km we got another 6h30 and now for another 100 km only an additional 7h. With a limit of 27 hours in total, 400 km presents twice the distance of 200 km and you have exactly twice as much time – so there is no bonus or progression of the time period available successfully completing the ride. This means that if you were getting through the 200 with some time to spare and then you were within minutes of the time limit with the 300, you will find it very difficult to cope with the 400, because you will not have a moment for additional rest and meals and that would mean that you will spend up to 27 hours on or by the bike, which means that you will have to be awake for about 30 hours in a row – with a good portion of night riding. For most people, this is quite a stressful idea, even without additional physical effort.

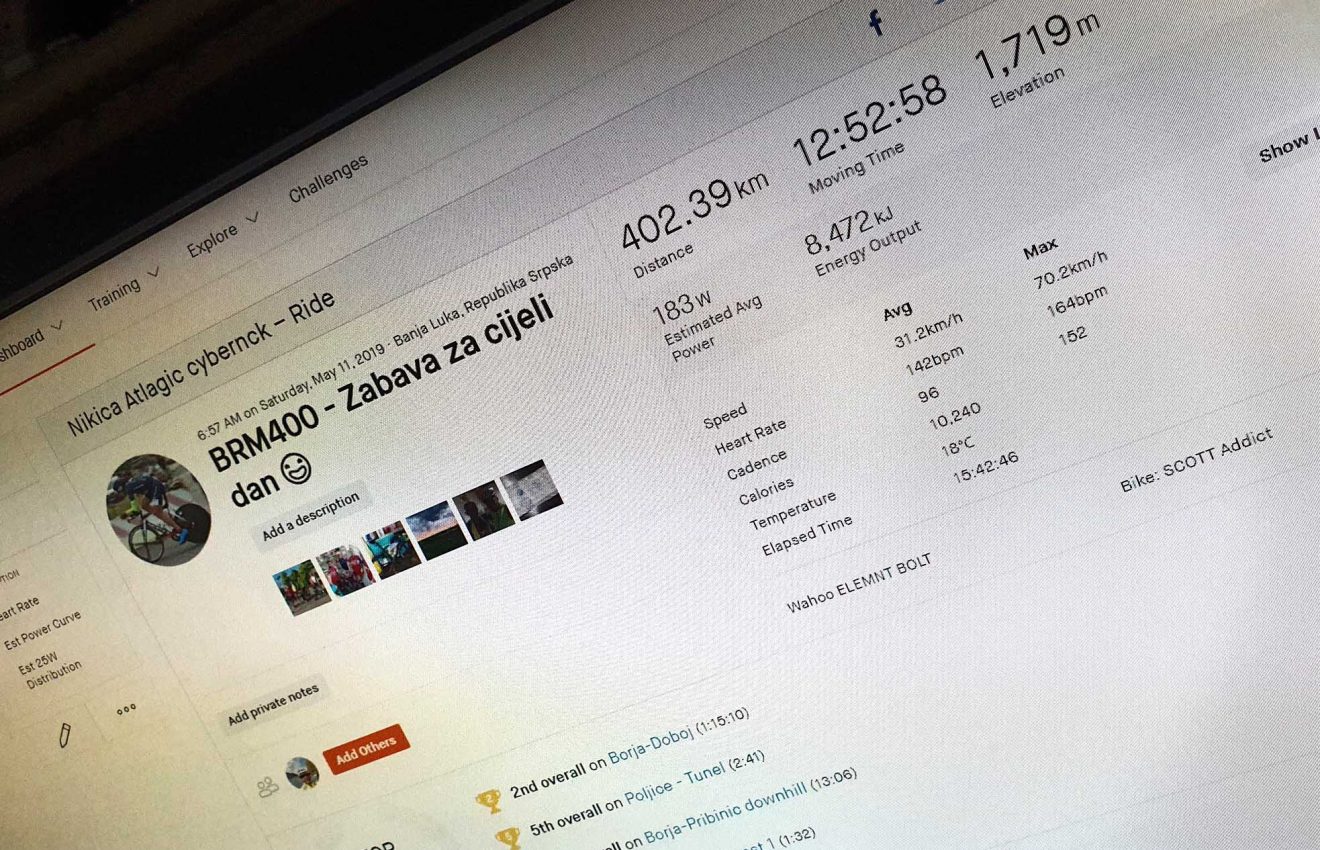

On the other hand, let’s take a look at someone who is really well prepared, rides very fast and pauses very seldom – he certainly rides that distance in one piece and in rhythm as he rides 200 and 300 km distances, so for such a person the time limit does not present a problem, nor does he need to endure such a long period without sleep, but it is certainly exhausting for the body when the heart spends 13-14 hours constantly running this heart rate zone.

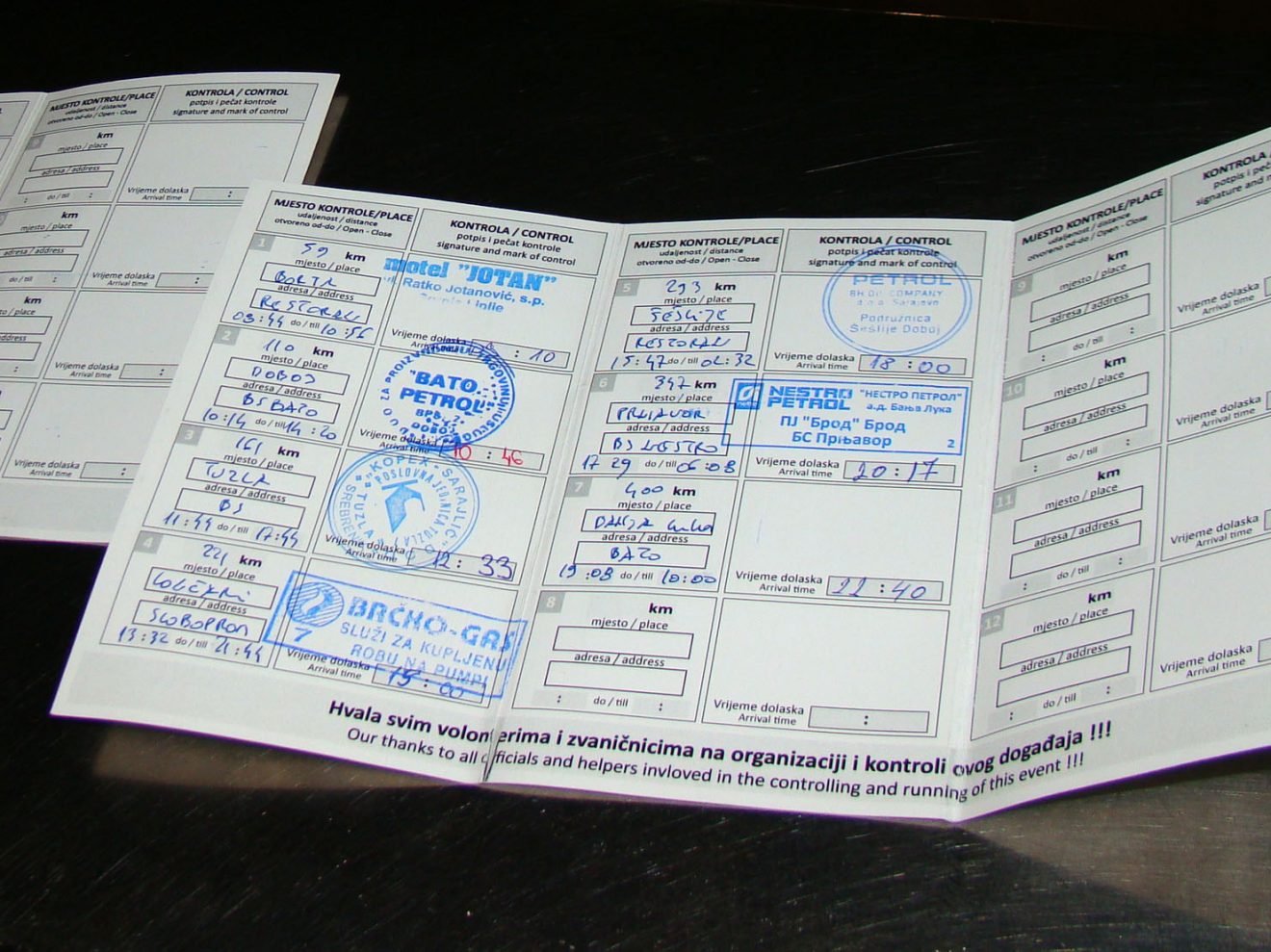

However, if we do not observe extremely slow or exceptionally fast riders, nor very demanding or very flat courses, nor extreme weather conditions (snow or negative temperatures) – then, if we focus on the average route and solid ultradistance cyclists – we will have the case that the riders usually complete the 200 within 9h to 10h30 and the 300 within 14-17h. Based on this information, someone will think: “Well, I’ll do 250-300 km in 15 hours, sleep 5 hours, avoid a good part of the night and have another 7 hours to finish within the time limit.” Well, that’s not really the case, at least when it comes to brevets/audax. Let’s remember that there are opening and closing hours for each checkpoint.

“I beg your pardon – when do you close?”

Let’s look at the scenario in which you decided to play it safe – you got up around 5 AM to get ready and arrive on time for registration and start of the ride, which for the purposes of this example is at 7 AM. You planned to ride all day or practically for about 15 hours, so that, with a short night ride, you could get into the accommodation until 10 PM, which is located on the approximately 270th km of the route. You’ve left yourself plenty of time for both a moderate pace of riding and a possible tire change and for lunch. Everything went fine, so you arrive at the accommodation around 9 PM already – leisurely explain to the host as to why you look like a Christmas tree on wheels, you get undressed, browse social networks, smugly glance at the brevet card and then… HORROR! You realise that, regardless of the fact that you still have 12 hours to reach the finish line, the next checkpoint, which is located on the 300th km of the route, closes at around 3 AM!

In a rush of panic, you do the math: “It will take me about an hour and a half of riding to make sure I’m not late at the CP. However, there is this hill that I wanted to avoid riding in the dark and what if get a flat tyre just then (and Murphy’s Law says it will) and I don’t even have enough time to recharge the flashlight!”… and suddenly you realize that you need up to 2 hours of riding to the next checkpoint, which means you have to be out of the accommodation and on bike no later than one hour after midnight while it’s already 10:30 PM. You can neither fall asleep nor will it help you, because anything more than the so-called powernap, i.e. 15 minutes of sleep and less than 3 hours of sleep in one piece will only make you groggy. You have no choice, you will lie down for a while and then continue riding according to the new plan or even earlier, you will arrive like a zombie at the specified checkpoint and then you’ll have another 100 km that awaits you before reaching the finish line.

If we consider the case that you are familiar with the previous scenario and that the first thing you do upon receiving the brevet card is to analyze the checkpoints – again, the situation is not much more favorable. Although it is practiced that checkpoints are properly distributed every 50-70 km of the route, this is not a mitigating circumstance. Let’s take a look at another example – one of the checkpoints in the second part of the ride is at 250th km, which is “too close” for you to stop at, so you plan on riding to the next one, which is, say, at 320th km. It stays open until about 4:20 AM, which does not present a problem, because you will definitely arrive there earlier.

However, what “earlier” means, depending on the circumstances, is a period between 11 PM and 1 AM. And so, you’ve arrived at that long-awaited checkpoint, most likely a gas station that may or may not be open – or it’s just a photo checkpoint. In any case, it is probably not a place where you can rest fairly or even at all and any accommodation will be a problem to find at that time, especially in rural areas, nor would it make sense to settle with just 80 km remaining to the destination, especially if you need to ride a further 10-20 km in order to reach the accommodation.

If the weather is very pleasant, you can lie down on a meadow, on a bench or in a canal, but otherwise – all you can do in that case is to continue riding slowly and finish the brevet between 3 AM and 7 AM, e.g. with the total time between 20h and 24h. If you also had some rain along the way, as well as colder weather, you’ll possibly start experiencing knee pain and have a feeling of a hole in the stomach because you haven’t eaten for more than 12 hours – and in the end you won’t have much satisfaction and a sense of accomplishment, having ridden and finished this brevet.

Success is the sum of small efforts

A good plan makes for getting half of the work done, so concentrate a little bit on the preparation before the realisation and appearance at the start line.

First of all, take a good look at the route, study all the ascents and supply points. Try to calculate where you should be on the route at what time and take a mental note or write it down, so that you know exactly where you are during the ride in relation to the planned pace. That way, you will always know where you stand with arrivals at checkpoints, as well as whether the planned food and accommodation options will be available to you.

I have stated many times so far in articles that it is always of my utmost priority to have enough nutrition with me or to have a good re-supply plan. With the 400 brevet, this is a particularly important aspect, as it is easy to overlook that after a certain hour, especially in rural areas, you will not be able to buy something to eat or drink. So you definitely need to plan ahead, get resupplied while you can and then ride without pressure. For this reason, it will be very useful for you to have purposeful bikepacking equipment with you on your bike.

In addition, we have already established that you will be on the road for a good part of the night and maybe even all night. With that in mind, you need to have tested bike lighting equipment, first to see where you are going and secondly to have functional lighting for long enough – which is especially important to emphasize, because many models of USB rechargeable lights can not last all night in some usable lighting mode and mostly can’t even function while in charging mode. This also applies to lamps with replaceable batteries, but you can bring a spare set of batteries for them. The same logic should be applied to the rear lamp.

In addition, the vast majority of GPS devices will not last 400 km without needing to be recharged by a powerbank and with the use of mobile phone with display set at maximum brightness during the day, it will probably need additional “juice” as well.

As I mentioned, at such a long distance and riding time, you can always face passing or longer-term weather troubles, as well as drastic changes in temperature, so it’s definitely handy to have extra layers of clothing at your disposal, as compared to shorter brevets.

“Oh, you’re so negative!”

Au contraire, Rodney! The purpose of these articles is to show you what can happen on rides like this, so you would be prepared, at least to the extent that it is possible to achieve in theory like this but the above examples are based on the rides of fellow ultradistance riders (names are fictitious and any resemblance to real events is coincidental :)).

It is worth mentioning that this distance is “adorned” by a fairly large number of withdrawals, compared to other brevets. The reasons are obvious – add to all the circumstances the possibility of unfavorable wind, showers or prolonged rain, a route that is harder than it looks “on paper”, unpreparedness with clothing, mechanics, electronics or you as a rider – and you can easily get in a lot of trouble.

Having stated all the negative circumstances and having made some suggestions, I must say that in the end the limit is always only in your minds, so with a little will, luck and a good reason for doing a 400 km brevet, there is no reason for you not to finish it. Fortune favours the brave – always keep that in mind and best of luck to you!

Let’s continue in an even stronger rhythm! The following article will be about riding brevets at distances of 600 and 1000 km!